Vacuum-Assisted Delivery: What is it?

Imagine you are in labor and you’ve been pushing for hours. The doctor brings up the idea of using forceps or a vacuum to deliver your baby.

Did you imagine horror music and picture metal instruments attached to your baby’s head? If so, take a deep breath. It’s not that scary.

Vacuum-assisted delivery

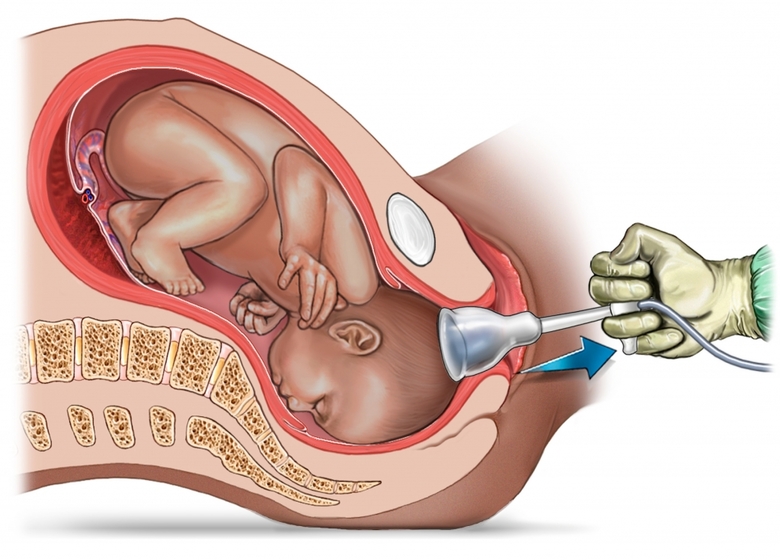

During vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery, your doctor uses a vacuum device to help guide your baby out of the birth canal. The vacuum device, known as a vacuum extractor, uses a soft cup that attaches to your baby’s head with suction.

As with any other procedure, there are risks associated with vacuum-assisted delivery. Even normal vaginal deliveries can result in complications in both the mother and the baby. In most cases, the vacuum extractor is used to avoid a caesarean delivery or to prevent fetal distress. When performed properly, vacuum-assisted delivery poses far fewer risks than cesarean delivery or prolonged fetal distress. This means the mother and the baby may be less likely to have complications.

The vacuum extractor has been used extensively in recent years, and the risks of vacuum-assisted delivery have been well-documented. They range from minor scalp injuries to more serious problems, such as bleeding in the skull or skull fracture.

(Read: C-section vs. Normal delivery – How are they different?)

Maternal Exhaustion

The effort required for effective pushing can be exhausting. Once pushing has continued for more than an hour, you may lose the strength to successfully deliver. In this situation, your doctor may provide some extra help to avoid complications. A vacuum extractor allows your doctor to pull while you continue to push, and your combined forces are usually sufficient to deliver your baby.

Maternal Medical Conditions

Some medical conditions may be aggravated by the efforts of pushing during labor. They can also make effective pushing impossible. During the act of pushing, your blood pressure and the pressure in your brain increase. Women with certain conditions can experience complications from pushing during the second stage of labor. These conditions include:

- extremely high blood pressure

- certain heart conditions, such as pulmonary hypertension or Eisenmenger’s syndrome

- a history of aneurysm or stroke

- neuromuscular disorders

In these instances, your doctor may use a vacuum extractor to shorten the second stage of labor. Or they may prefer to use forceps because maternal effort is not as essential for their use.

Prerequisites for Vacuum-Assisted Vaginal Delivery

Several criteria must be met to safely perform a vacuum extraction. Prior to considering a vacuum procedure, your doctor will confirm the following:

The cervix is completely dilated

If your doctor attempts vacuum extraction when your cervix is not fully dilated, there’s a significant chance of injuring or tearing your cervix. Cervical injury requires surgical repair and may lead to problems in future pregnancies.

The exact position of your baby’s head must be known

The vacuum should never be placed on your baby’s face or brow. The ideal position for the vacuum cup is directly over the midline on top of your baby’s head. Vacuum delivery is less likely to succeed if your baby is facing straight up when you’re lying on your back.

Your baby’s head must be engaged within the birth canal

The position of your baby’s head in your birth canal is measured in relation to the narrowest point of the birth canal, called the ischial spines. These spines are part of the pelvic bone and can be felt during a vaginal exam. When the top of your baby’s head is even with the spines, your baby is said to be at “zero station.” This means their head has descended well into your pelvis.

Before a vacuum extraction is attempted, the top of your baby’s head must be at least even with the ischial spines. Preferably, your baby’s head has descended one to two centimeters below the spines. If so, the chances for a successful vacuum delivery increase. They also increase when your baby’s head can be seen at the vaginal opening during pushing.

The membranes must be ruptured

To apply the vacuum cup to your baby’s head, the amniotic membranes must be ruptured. This usually occurs well before a vacuum extraction is considered.

Your doctor must believe your baby will fit through the birth canal

There are times when your baby is too big or your birth canal is too small for a successful delivery. Attempting a vacuum extraction in these situations will not only be unsuccessful but may result in serious complications.

The pregnancy must be term or near term

The risks of vacuum extraction are increased in premature infants. Therefore, it should not be performed before 34 weeks into your pregnancy. Forceps may be used to assist in the delivery of preterm infants.

Risks for the baby

-

Subgaleal hemorrhage

The blood accumulates in a larger portion of the skull, under the scalp, due to improper suction. Infants may have a swelling crossing the suture lines, a boggy scalp, and an expanding head circumference. They might also have the signs of tachycardia, pallor, hypovolemia, and a falling hematocrit. This condition occurs in about 1 to 3.8% of vacuum extraction cases.

-

Scalp lacerations and swelling

Small breaks in the skin or cuts on the scalp caused due to multiple detachments of the suction cup. These wounds quickly heal without leaving any marks. The suction uses a lot of pressure to pull the baby’s head, which results in a swelling giving a cone-shaped appearance to the head. This goes away in one or two days after birth.

-

Cephalohematoma

It occurs in 14-16% of vacuum-assisted deliveries. It happens when bleeding occurs between the skull and the membrane beneath the skin.

-

Intracranial hemorrhage (bleeding inside the skull)

It is found to occur in one out of every 860 vacuum-assisted deliveries.

-

Retinal hemorrhages (bleeding in the back of the eyes)

It occurs most commonly with vacuum-assisted deliveries and is associated with prolonged labor. It resolves within a few weeks.

-

Transient neonatal lateral rectus paralysis

It occurs more frequently and in around 3.2% of vacuum-assisted deliveries. It resolves voluntarily.

-

Brachial plexus injuries

It is associated with nerve damage.

-

Developmental delays

Delays in the development of gross motor skills, fine motor skills, language skills, cognitive ability, and social skills.

-

Cerebral palsy

An injury to the brain that causes impairment of movement and motor functions.

-

Chignon

A swelling caused in the area where the suction cup is attached. It gets resolved within two to three days.

-

Neonatal jaundice

It occurs when the blood accumulated by the breakdown of the blood vessels, caused due to vacuum extractor, is reabsorbed by the baby’s body. This results in increased production of bilirubin. It adds to the burden of the baby’s liver, which is still not fully developed, hence leading to neonatal jaundice.

-

Shoulder dystocia

This happens when the baby’s shoulder gets stuck behind the mother’s pelvic bone due to an improper vacuum pull.

To avoid these risks, you have to try and minimize the need for a vacuum-assisted birth. Next, we tell you about the measures to avoid vacuum-assisted delivery.

How To Avoid A Vacuum-Assisted Birth?

Here are a few tips you can follow to avoid assisted vacuum birth:

- Stay healthy and fit.

- Ensure that the baby is in an optimal position, with the help of an ultrasound scan.

- Take enough rest before labor, since you will need energy during labor.

- Avoid lying on your back and stay upright during the labor.

- Eat well and keep yourself dehydrated to reduce the chances of exhaustion.

- Learn about the active positions of labor such as squatting, lunging, and kneeling.

- Avoid taking epidural as it can prolong the labor and you may not be able to feel the contraction or push when you need to.

Vacuum-assisted delivery is an option for deliveries that have gone on too long or need to happen quickly. However, it does create more of a risk of complications for the birth and potentially for later pregnancies.

While making a birth plan, you can learn about your delivery options and let your physician know what you are comfortable with. Be sure you are aware of these risks and speak to your physician about any concerns you have.

Also read – Episiotomy and when is it Needed?